Delaware Bend is near the banks of Lake Texoma seven miles north of Dexter in northeastern Cooke County.

At one time, Delaware Bend had a post office and a school.

The town was named for the bend of the Red River where the community was located.

It served as a church community for area farmers and ranchers.

In the 1940s, the community lost three-fourths of its land to Lake Texoma, and the school was consolidated with the Dexter school district.

Some years ago, Dexter resident Wes Dick wrote a book entitled “The Life and Death of Delaware Bend.”

It was dedicated to chronicling the history of the area and its people.

The following is an excerpt from chapter four, “The Story of Junior Wendt.”

It is a compilation of oral history from Wes’s father Hal Dick with research and contributions from Wes himself.

***

The Story of Junior Wendt

My name is Hal Dick. I was born in Delaware Bend in 1924. Because of the Great Depression of the 1930’s and the poverty it brought to farm communities everywhere, I guess I had a pretty hard childhood. But I did not know it at the time.

As a kid growing up in Orlena, another name for Delaware Bend, I felt I had a good life. We had no money but no one else did, either. We did not know any different. We always had plenty to eat, and we had lots of things to do.

I went to a one-room schoolhouse. All the kids went to it up through 9th grade. For grades 10 and 11, we then rode the bus to Whitesboro. There was no 12th grade at that time.

We could hunt and fish and ride horses. We picked up pecans to sell and picked wild grapes for jelly. Even as kids, we could travel and explore for miles up and down the river. Other than watching for rattlesnakes, we did not have to feel afraid or in danger.

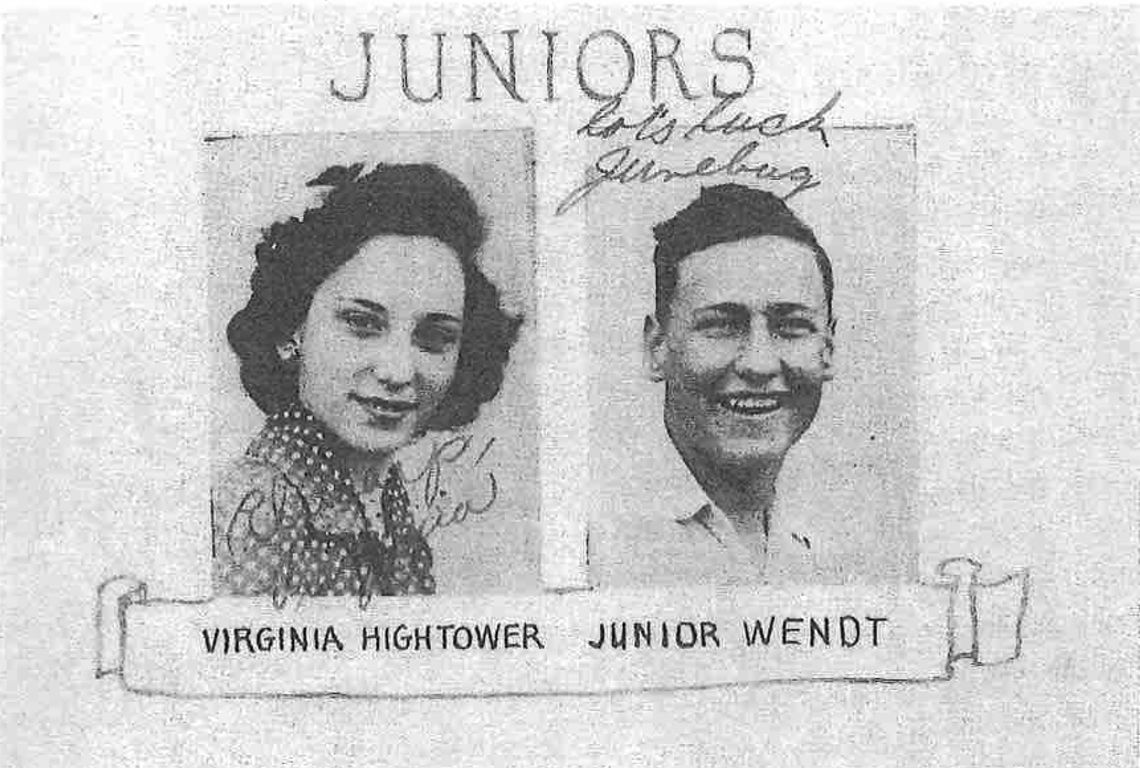

One of my friends growing up was Junior Wendt. His family lived down from us on the main road through Delaware Bend. We called him Junebug. I was one grade ahead of him. But for all practical purposes, we grew up the same way, at the same time.

When he was little, he tagged along with us bigger boys. The Wendts were all pretty tough and as he got older, he was able to keep up with us. We watched hawks fly during the day and listened to whippoorwills call at night. We were playmates and went to school together.

I mentioned the one-room school. It was called the Riverside School and it was located in the upper bottoms. Sort of the west end of Delaware Bend. It was one room, with a divider in the middle. One side of the divider was the “big” room. That was where the bigger kids studied, grades 5 - 9. One teacher taught them. The other side was the “little” room for the smaller children. The second teacher taught them.

Every Monday morning, the teachers would move aside the divider and we would have some type of program, such as public speaking or singing, with the students doing the program.

All of the kids from the upper bottom went to school there and that included Junebug and me.

We attended through the whole Depression there at Delaware Bend during the 1930’s. We started in the little room, graduated to the big room, and grew up together. By the time we went to high school at Whitesboro in the early 1940’s, World War II had started.

In addition, Lake Texoma was being built. That meant Delaware Bend would soon be under water. My family and our neighbors were all forced to sell out. People started moving away. So let us move to the fall of 1942.

Junior and I had both finished at the one-room school at Delaware Bend and we were both going to high school at Whitesboro. I was in the 11th grade, which was a senior then. I would soon be graduating and subject to the draft. WWII was going strong, and not very well for the U.S. at that time. Junebug was in the 10th grade.

Each day, for that entire school year, we rode the bus together from Delaware Bend to Whitesboro. Now this was not your typical, modern-day, smooth-road bus ride. It was a hard, daily, 96-mile endurance contest. It was two hours every morning and two hours every evening.

Being on the “end of the line” at Delaware Bend, we were the first ones on and the last ones off. I often said l never saw daylight, at home, all winter. It was dark in the morning when I boarded the bus and dark when I got home. The roads were too rough to even think about studying.

So, for four hours every day, the kids from Delaware Bend visited with each other. One of the main things Junior and I talked about was the war. He wanted us both to volunteer for the Navy and get on a ship together. He had grown up at Delaware Bend and he was interested in “seeing the world.” Plus, Delaware Bend was being torn down and abandoned right before our eyes.

In addition, the war was bad at that time, 42-43, and we were going to be drafted anyway. So, he wanted us to join the Navy together. He liked the idea of being in the war with a friend.

At that time, I was a few months from graduation there at Whitesboro.

Junior still had one more year to go. But he would get credit for that last year by being in the military. In other words, he could join and still get his diploma. I did not share Junior’s enthusiasm for immediately going into the service.

My father was a rancher and we had to move our cattle out of the bottoms first. Fences were not good in those days (there was no fence next to the river), so rounding up all the cattle was more than challenging. Plus, I was more interested in the Air Force when I went -- not that I was in a hurry to go. So, I could not go along with Junior’s plan for us to join the Navy together.

I graduated in May of 1943. Because we had cattle, I was given a temporary deferment. I began tending, and later rounding up and loading, cattle. My parents and my younger brother and sisters all moved out, as did most of the families who had been forced to sell out. We were the families living nearer the river, like the Wendts, who would be flooded when the lake filled.

By the fall of 1943, I was one of the few people still living down at the lower elevation. Besides tending to our own cattle, several of the other ranchers, who had cattle they were unable to load out, had herded theirs over with ours. Plus, a few outside people had just moved cattle in to pick up free grazing after the ranchers left, but before the lake filled. So, it was something of a “community” herd.

You might think it was pretty quiet there with so many people gone, but just the opposite was true. There was a P.O.W. camp at Gainesville. So, during the week, the Army brought German prisoners out there to “clean up.” That way, when the lake filled, there would not be hazards, such as houses, barns or big trees in the water.

On occasion, the Army would let me guard a couple of prisoners assigned to some job, such as tearing down a barn. For helping, I got to eat with them, a real treat for me since food was a problem out there at that time. And the Germans never tried to escape or anything. I think they realized they were better off at Delaware Bend than on a front line in Europe.

On Saturday night, l would go to town in Whitesboro. And I would often see Junior. He had started his last year of high school by then (fall of 1943). We would talk. He still wanted to join the Navy. In hindsight, I wish I could have talked Junior out of joining. At the least, I might have convinced him to finish high school first. But hindsight is always 20/20. And like Junior, I had plenty to think about, too; the war, the draft, the lake, the cattle and all of my friends and family scattered in every direction.

In that sense, going into the Navy seems like a good idea for someone who grew up on a river. There is a comfort around water.

***

On March 12, 1944, while still a member of the Whitesboro High School senior class, William Jennings Bryan Wendt, Jr. enlisted in the United States Navy. At graduation, his diploma was issued to him in absentia. He received his boot training at San Diego and was then sent to torpedo school at Keyport, Washington. He trained for eight months before leaving for sea duty at Christmas 1944. Wendt would be assigned to the USS O’Brien.

The USS O’Brien (DD-725), an Allen M Sumner-class destroyer, was a workhorse of WWII. In June of 1944, she saw duty during the invasion of Normandy (D-Day). While battling a German shore battery, she took a direct hit and lost 13 men near Cherbourg. After repairs, she moved to the Pacific Theater and the Philippines.

In January of 1945, she supported the landing shown in the above photo. Luzon is in the Philippine Islands. Destroyers like her had numerous duties. They bombarded islands, such as Iwo Jima, to “soften them up” before ground troops stormed the beaches. They helped protect larger ships, like aircraft carriers, from submarines, enemy ships, and, perhaps most importantly at that point of the war, kamikaze attacks.

Kamikazes were Japanese suicide pilots. They flew planes loaded with bombs into enemy targets, such as ships. And the pilot did not bail out. The idea was to set off their own bomb while also setting off secondary explosions on the ship, such as its ammunition stores. Whether he hit his target or was shot down trying, it was a one-way trip for the kamikaze pilot.

Finally, a destroyer like the O’Brien had to protect herself from attack. At that point of the war, January 1945, the war in Europe was looking up. Fighting was still fierce, as in the invasion of Germany, but the end was in sight.

Over the next few months, the Germans would surrender, the concentration camps would be liberated and the fighting would stop in Europe. Not so in the Pacific. In fact, it was just the opposite. The Japanese were “dug in” on several groups of islands. One group was the Philippines.

Another group was south of Japan, with Okinawa the best-known. They were also holding a number of volcanic islands further east, out in the Pacific. The most famous of those was Iwo Jima. Being so close to Japan, the Japanese, who were inclined to fight “to the end” anyway, were even more inclined to do so a few miles from their own shores.

On Jan. 6, 1945, while preparing for a landing of Army assault troops at Luzon, a Japanese aircraft crashed into the port side of the O’Brien. The damage, though significant, was not bad enough to immediately disable the ship. She continued escorting other ships and bombarding the shore for several more days.

On Jan. 9, troops landed.

Afterwards, the O’Brien went to Manus Island for repairs. She rejoined fleet carrier forces a few weeks later, on Feb. 10, 1945. She was providing her normal support, this time for air strikes against Tokyo, lwo Jima and the Bonin Islands. She was also performing shore bombardment for island troop landings.

The battle for Iwo Jima is immortalized in the most famous picture of WWII, four soldiers raising an American flag on Mt. Suribachi. That picture was taken Feb. 23, 1945. And the O’Brien was an important part of that Pacific fighting. The loss of life during the fighting for Iwo Jima, and nearby islands, was almost beyond belief. And even though the sacrifices of the ground troops are most remembered, the danger to the men on ships was no less real.

Under frequent kamikaze attack, and under the constant threat of it, the ships were, to some degree, sitting ducks. For defense, they had their anti-aircraft batteries, help from nearby ships, and American aircraft that patrolled especially on the lookout for kamikazes. But consider a day with, as an example, low clouds. A squadron of Japanese planes could approach a ship without being seen.

The Japanese, who had refined their kamikaze techniques by that point in the war, had learned that when multiple kamikazes attacked the same ship, the chance of at least one hitting the ship was much greater. So they would, as an example, attack with a lead plane. While it was drawing fire, other planes would make a run at the ship, perhaps from low clouds. That was all happening within a matter of seconds. When two or more planes came in on the ship at once, the sailors did not have time to deal with all of them. Even with air support, the American pilots and the gunners on the ship might have only seconds to target a diving bomber--in low visibility--as their own ship turned. And it only took one getting through to cause catastrophic damage.

The fighting around Iwo Jima subsided (at least when compared to what it had been) during March 1945. U.S. forces were then able to attack progressively closer to Japan. The plan was to establish bases near Japan, for future attacks deeper into the Japanese home islands. To establish those bases, the U.S. had to take control of a number of strategic islands, including Kerama Retto.

As the Americans got closer, the Japanese fought even harder, if that was possible. Plus, by being closer to Japan, American ships and troops were easier targets. The Japanese did not have to fly nearly so far looking for them.

With the end of March approaching, the O’Brien found herself off Kerama Retto, near Okinawa, Japan.

***

On the morning of March 27, 1945, Junior Wendt was a 17-year-old seaman first class. As a member of the O’Brien crew, he found himself among an important and large class of military men -- battle-hardened 17-year-olds.

For one year, he had “seen the world,” while getting away from that 96 miles-per-day school bus ride. For three months, he had been on sea duty. That is what he wanted and it gives me some comfort as I finish his story.

At the same time, I have to think of the situation he was in. He was fighting an enemy on their home field, who would die before giving up. He was fighting an enemy who would take as many American lives as possible in the process.

And he was half-a-world away from the only home he had ever known, which was being taken to build a lake.

Though we both thought we were “grown up” at 17, it now seems a lot to ask of him.

***

Ships keep logs. A former O’Brien crewmember, Wayne Meddley, posted the following to the O’Brien deck log for March 27, 1945.

DECK LOG - REMARK SHEET USS O’BRIEN (DD725)

4 - 8 Watch

Steaming as before in patrol area F-3 off Kerama Rhetto, steering various courses and speeds to contemn to patrol area.

0403 Secured from General Quarters, no unidentified aircraft in the vicinity, set condition III watch, material condition Baker.

0545 Detached by CTG 51.1 and ordered to report to CTF 52 in accordance with instruction in CTF 52 Operation 2-45. Proceeding on various courses and speeds to rendezvous with Fire Support Group #3 in Fire Supply Area #5 off Okinawa Island.

0618 General Quarters for air aler.t

0623 Sighted enemy fighter planes diving on the ship; opened fire with all available guns. Plane burst into flames and crashed about 100 yards on the starboard beam.

0624 Another enemy fighter seen diving on the ship. Maneuvered radically attempting to bring forward battery to bear, opened fire with all available guns.

0624.5 Enemy plane crashed into superstructure amidships, port side, tearing through superstructure to starboard side…

Following damage caused:

Main radio completely demolished, CIC wrecked and all equipment either badly damaged or destroyed, all radars destroyed, both sound stacks damaged and gear inoperative.

Starboard 40mm twin demolished, port 40mm twin damaged and inoperative.

One forward 20mm destroyed.

Starboard torpedo director damaged and inoperative.

Number one fire room out of commission due to completely demolished intakes and damage to steam and feed water piping.

Number two boiler completely flooded.

Forced draft blowers 3 and 4 badly burned.

All electrical circuits and equipment demolished from midships to passage to wardroom and upward from main deck.

General area frame 65 to 100 both sides, main deck starboard side dished in one foot and ripped along seam frames 75 to 95.

Spaces demolished: - wardroom, pantry, galley, provision issue room, torpedo workshop, log room, sick bay, laundry, uptake space forward fire room, starboard side of sound hut and CIC Radar transmitter room, forward 40mm ready service room, radio central.

Forward stack damaged beyond repair.

Superstructure deck ripped up from Frame 85 to 100.

Starboard side 40mm gun deck blown up 20ft. Salt, fresh water and high-pressure air lines in damaged area beyond repair.

Starboard side after bulkhead forward fire room warped, bulkheads to #1 and 3 blower rooms warped in vicinity of main deck....

***

Junior Wendt was killed three weeks before his 18th birthday. The Navy buried him at sea where he might find comfort near the water.

“Yes, we’ll gather at the river,

the beautiful, the beautiful river;

gather with the saints at the river

that flows by the throne of God.”

-Robert Lowry

***

Hal Dick passed away in 2015 at the age of 90. He was a retired educator having served as superintendent at Callisburg and Era ISDs. He also served as an administrator at Gainesville ISD as well as a vocational agriculture teacher. According to his obituary, he was also the unofficial fire chief at Era because the fire truck was kept in his back yard.

Austin Lewter contributed to this story.